palimpsest

-

a manuscript or piece of writing material on which the original writing has been effaced to make room for later writing but of which traces remain.

-

something reused or altered but still bearing visible traces of its earlier form.

“Sutton Place is a palimpsest of the taste of successive owners”

-

I feel a little dirty.

I have abandoned my large and medium format cameras and have come to question my long-held beliefs in the principles of pure photography as laid down by the titans of the West Coast Photographic Movement. I haven’t touched any of my other cameras since I started shooting with a Fujifilm instant camera in November. Not my Mamiya C330 or my Arca Swiss view camera.

Setting aside the hyperbole…

Instant film is sweeping the nation; Instax film was the highest selling camera item on Amazon.com during the holidays.

And I’ve been trying to figure out why I caught the instant film bug.

Up to this point, I have couched my work in a term that photographer Edward Burtynsky coined — “the contemplated moment” — in contrast to Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment.” Burtynsky means to describe the slower process with his 4×5 and 8×10 view cameras. Because of the camera weight and numerous steps involved before exposing film, one is habituated into a state of accumulated photographic intentions. That is, tending to do a lot of the compositional, conceptual and camera placement deliberations “in the mind’s eye” as Ansel Adams would say, prior to photographing.

I have been working with large format film cameras since 2005, and felt that I achieved competence with their technique in 2009 during a trip to the Midwest to photograph industrial architecture and create portraits for my American Traditions project.

Despite my attention grabbing in the beginning of this post, I’m by no means abandoning large format, but my reaction to using the instant camera is illuminating the motivations behind my practice and opening up new means for expression.

Additive is Addictive

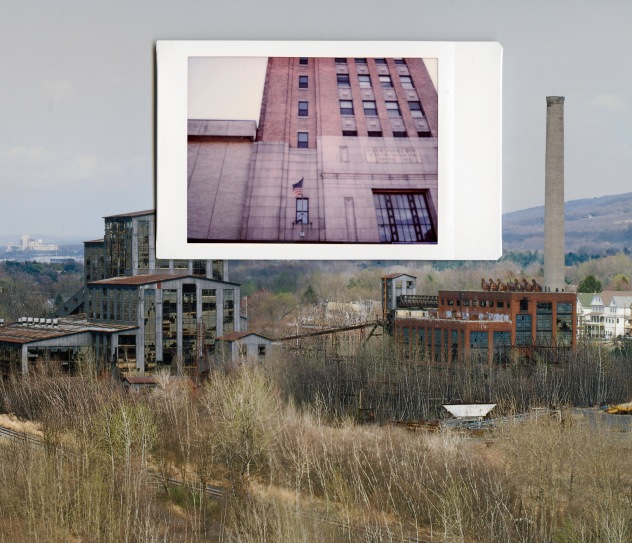

Here the photographer has added his Instax print over a surface and photographed it. This creates a dialogue between the subject of the picture and the material with which it is combined, or overlaid. This additive technique is interesting me because of my background where the conceptual framework of a photograph lies between images within a series rather than a dialogue between two different picture elements within a single frame. Below are a few of my additive overlays:

I’ve long held that reinforcing meaning in one’s work to be the most direct route towards effective meaning, and this additive technique with instant prints is a valuable tool in exploring how two picture elements can interact within a single frame. Whether or not you agree with Gary Winogrand’s assertion that pictures don’t tell stories, it would be hard to argue that pictures don’t describe things well; and I’m enjoying demystifying the surface of my pictures (for some I am drawing from the public domain) and breaking the temporal wall between two separate pictures.

Photography, often neither an additive or subtractive art form, is usually a three fold process: Capture the picture, edit it for impact, and place it within a series. The identity of the original solitary picture is rarely altered. But when I modify the surface with another image, the additive element often reinforces meaning, and the white border found in the Instax material proves to be a simple and effective element to indicate duality.

“Let reason govern thy lament.” -Marcus, Titus Andronicus